The Slingshot Effect On The Piano, Or How To Increase The Tempo Of Your Piece When Nothing Works.

Do you know what is the most common thing students and pianists want to achieve with their pieces? Is it to make them softer? To make them more convincing, perhaps? Well, none of those noble things. In my minute experience as a piano teacher and aspiring pedagogue, what most students want most of the times, is to make their pieces faster.

That’s good, though! Besides, I do not know of any pianist (dead or alive) that was considered a great by just playing second movements of sonatas. Do you know of any? Most of the pianists that we consider great are the ones that play, as an old friend used to say, frantically.

You’ve got to play frantically if you want to be considered the next Michelangeli in this show-offy world. You will never achieve true greatness with second movements, nocturnes, adagios and the rest of lesser pieces the professional musician secretly despises and frowns upon – well, when you ask a pro pianist if they like second movements and slow pieces they would bend over backwards to persuade you they do like them. But they fully well know those pieces won’t cut the mustard in the 21st century pianistic arena. You’ve got to play frantically… Welcome to human superficiality.

So, it’s no surprise that most of my students always want to notch up their speed and always feel that their playing is not sufficient to enter the sphere of real pianism.

“I have to play it faster, sir,” they would say.

“Oh, I wish I could play it as fast as you, miss.”

“This pianist on YouTube plays my study in less that a minute!”

And so on and so forth – you get my gist. By the way, they never seem to say, “I wish I could play it more slowly and poised, sire.” Oh, well.

❦

But enough of my rumbling and let’s get on with the franticness of our pieces.

So, for the purpose of this article, the initial problem a student wants to solve is how to increase the speed of a piece that doesn’t seem to get any faster. Here’s how most students would practice; they would start from practising the piece at their current fastest speed, and then they would try to push the tempo forwards, starting from that very speed. Most of the time the speed will not increase sufficiently, of course, especially if the piece is virtuosic. When they finally play the piece a little faster, it lacks clarity in both technical and musical articulation, and it feels unbalanced in its structure.

And so they despair.

They would come to their teachers confused, lacking of confidence. The teacher, more often than not, will resort to saying the same cliché things, such as, “play it a bit slower”, or “just keep at it”, or even, “your technique is not there yet” (Guilty your honor).

Playing slower is, of course, a sage thing to suggest. Who wouldn’t agree. But the secret here is how slow should they play. This is where I suggest my pupils to utilise my “Slingshot Effect”.

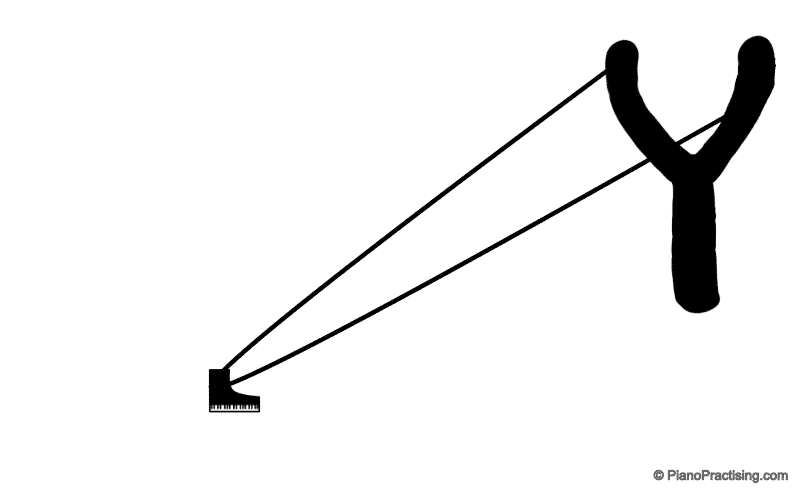

The Slingshot Effect

So, what is that slingshot effect that I so pretentiously advocate, then? To start, I would say that the slingshot effect is not a step-by-step analogous action of the slingshot transferred to piano technique. If I was to support this claim, I would significantly add to the preposterousness of this website.

The slingshot effect is just a sort of freely fashioned expression to get the student’s mind geared towards how they should practise.

To simplify the demonstration of this technique, I won’t use tempo markings but beats per minute (BPM). Follow the steps below with precision.

How the slingshot effect works

Say that your desired ultimate speed of the piece is at 120 BPM.

1. First, stop practising the piece at once. If possible, leave the piece to settle – Three days without practising it should be sufficient.

2. In your next practising session, practise the piece at 50% the speed you normally practise it. Not just a little slower, but close to 50% slower. Repeat at that slower speed for at least a couple of times. Example: You usually practise the piece at 100 BPM. You practise it at around 50 BPM. (Speed 1 = 100 BPM. Speed 2 = 50 BPM.)

3. Right after you complete part III from above, increase the speed significantly and closer to your intended speed of 120 BPM (perhaps increase to 115 BPM). Do not practise your piece at your usual speed (Speed 1).

4. Repeat steps 2 & 3, daily.

That’s it. You will miraculously increase the speed of your piece and, hopefully, keep it up there.

Why the Slingshot Effect Works

By significantly decreasing the speed of our piece, we allow our brain more time to contemplate its doings, and also let our fingers to “sit” better on the keys.

The slingshot effect reinforces the influence of good muscle memory practices and just leaves our minds free to apply speed.