Differences Between Rests and Phrases

In this article I am going to talk about the differences between rests and phrases and less how to play them.

But before talking about that, I would just say that, arguably, music has one of the largest catalogue of words to describe its ever-changing doings. And it is up to us to decide how to interpret those words, no matter what the current musical zeitgeist prescribes.

For instance, compared to classical ballet, which has a relatively smaller number of contextual interpretations of its directions, music’s musical directions (such as articulations and dynamics) are not only vast but also we use them in vastly varying styles of compositions.

Now and then, poor pianists find themselves confused by the very same musical directions they have met in a previous piece. For instance, the staccato on Rachmaninov should have a different attack and decay from the Staccato on Schnittke.

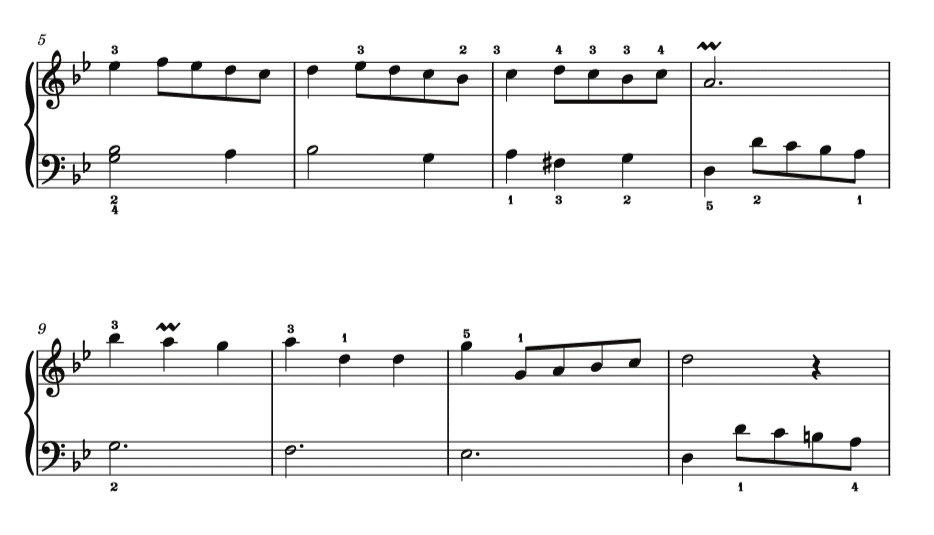

Piano teachers also find themselves drowned in a pile of similar musical directions, that often they need to be approached differently from composer to composer and even from piece to piece from the same composer. “Sir, what is the difference between this legato from the legato non troppo here?” How to play staccatissimo in this passage and what is its difference to the staccato from the previous bar? And, of course, you get more obvious, explanatorily, questions such as, “what is the difference in the legato here from playing the same passage leggiero there?” (Ex. See Crammer Opus 740, study in d minor). Often, the physical effort to explain those various directions is immense.

Anyway. Back to the rests & phrases. One of those questions I often get asked is what is the difference between a phrase and a rest. My students will argue that, since in both instances you would have to “stop” the sound, how then could we make them sound unique?

Again, as mentioned in the beginning of this article, it is left to us performers to decide the fate of what’s is written on the paper. However, let’s think for a minute, and decide on the definitions of rests and phrases before deciding on their performance attributes. Let’s start with the rests.

Now, rests are simply signs that tell us to stop producing sound — that’s the basic notion of a rest. Stop the sound. And then, of course, we would have to continue the “sound”, unless we are at the final bar of a composition.

Phrases, on the other hand, have a slightly more elaborate meaning.

- Phrases are musical chunks that contain a unique and concrete musical meaning

- Phrases could include rests within themselves

- Phrases could start after a rest

- Phrases could finish with a rest

- Phrases could finish after a rest

- Phrases could start without a preceding rest

- Phrases could finish without a rest

Go figure. And then talking about the hurdles of parkour.

How do we approach rests & phrases

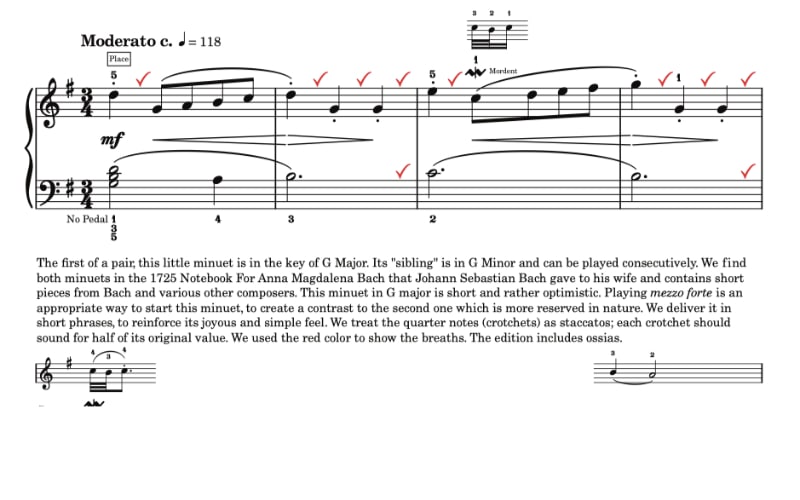

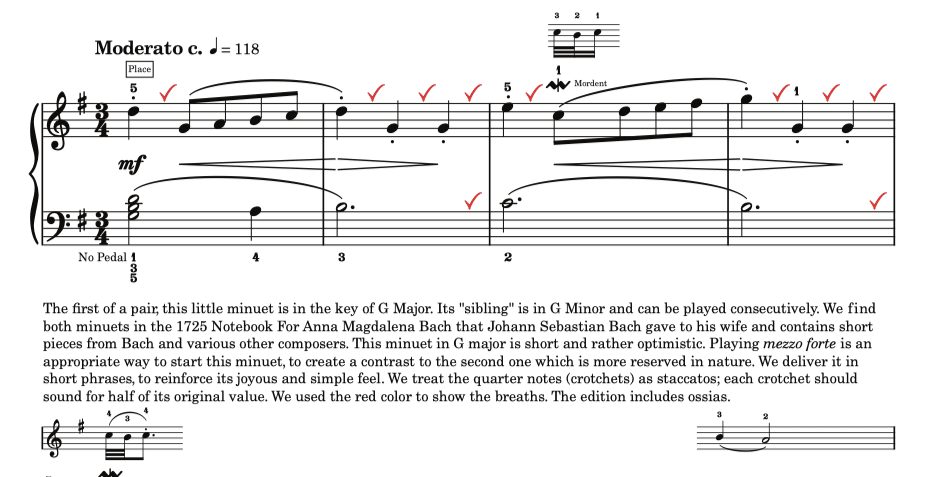

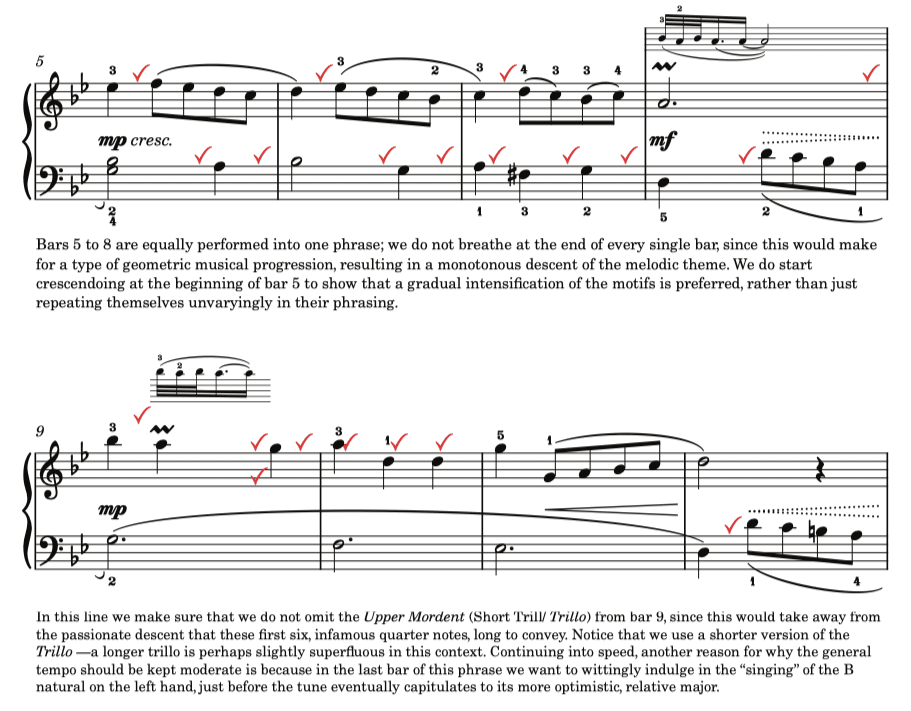

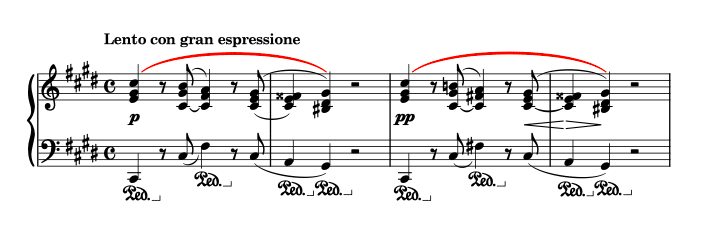

So, how do we play them rests and phrases?. Well, simply we play them, as the composer dictates. For example, a rest by Schnittke will be more abrupt and “rigid”, than rests from Chopin’s first four bars of his nocturne in C sharp minor, Op. posth.

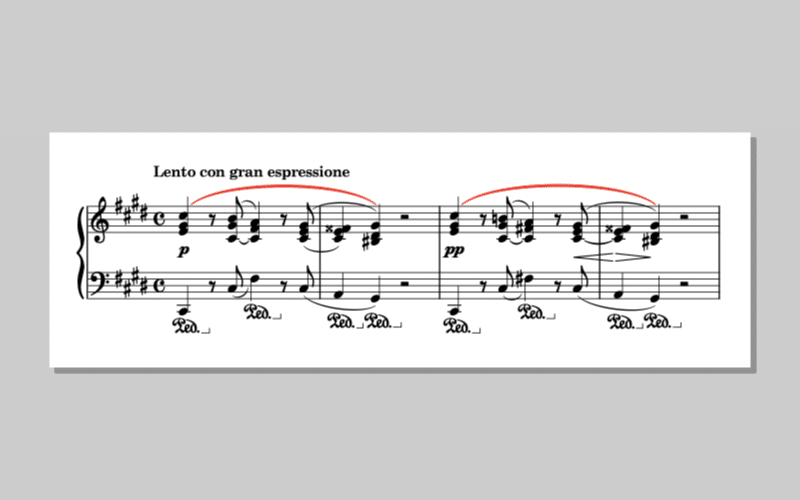

If we use this very nocturne by Chopin to elaborate, we reach the following conclusions:

- There are two main phrases in the four-bar intro of the nocturne (marked with a thickened red slur on figure 1)

- Those two main phrases have two bars each

- Within those main phrases there are rests

- Within each main phrase, there are three smaller “sub-phrases”

- Both phrases finish with rests

figure 1

So, again, coming back to our personal styles of interpretation and the choices we should have to make to perform a piece, we are being asked here to decide how to perform those rests within the phrases and, of course, how to perform those two larger phrases without making them sound fragmented. In my opinion, and since it is near impossible from a website to master musical performance, I would just say that we should try to preserve the oneness, per se, for each main phrase at all costs. And, at the same time, we should play the “veiled” rests as small breaths, helping us to define the larger meaning of the main phrases.

Copyright © 1st of February 2023, by Nikos Kokkinis

===========