Is the Quality of a Piano Performance Subjective?

What do you think….? *with a snobbish expression on my fat face*

Is the quality of the performance of a piano piece subjective? Indeed, is the cooking calibre of the female partner in a newly established couple less than great? Of course, not. It’s fantastic. Only after a few years of marriage, the now husband could possibly attempt to question his wife’s culinary expertise.

When we criticise anything and everything in life, there is always the subject of subjectivity lurking around — except, of course, if we could define mathematically all the elements that constitute the subject; which, in our case in music, it is close to impossible to achieve. Even if we ask someone how much is one plus one, for instance, they might get it wrong because there is still the element of the spontaneous erroneous judgement. Just go online to see with your own eyes the existence of the multitude of hilarious answers found online.

There is no certain answer to any question, so how do we expect a piano performance to be no less than subjective? And, don’t forget, no amount of proof will change the mind of someone who are wrong in their judgements, when they are determined to stand by their own principles, logic, or simply, false reckonings — for example, no matter how many people set foot on the moon, or how many interstellar missions send back to earth images of Jupiter in close proximity, there are always going to be the people who profess that the earth is flat. That’s why — I digress — I always maintain that when you go to a friend’s concert, find the performance of your friend absolutely great. Because, nobody can really persuade your friend concretely that it wasn’t. But I’ve written about this subject a lot in my years as a crass writer on Piano Practising.

What determines the quality of a piano performance, and why it is subjective.

The quality of a performance is always subjective because of the following factors:

- The pianistic capacities of the body judging the performance: For instance, your student’s performance in your annual studio’s concert in the local pub (yes, I’ve heard that choice of venue) could be less than “amazing”, if your student was judged not by your own mediocre pianistic brain or your student’s gullible parents, but by an YCA competition panel.

- The venue of the performance: An adjudicator won’t judge the same on every venue/competition. For instance, in a most hypothetical scenario, if a panel constituting of the same judges judged the same performers and their performances but on different venues or circumstances, the performers would undoubtedly get different treatment. In most cases, they would be judged more strictly on harder competitions.

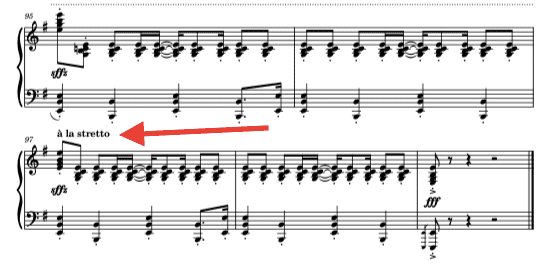

- The pianistic conventions of the era: For example, it’s customary to play Chopin’s Opus 10 No.1 in today’s rigid and fast-paced piano at a frantic tempo that pianos from Chopin’s era arguably could not handle.

So, do not worry too much about whether your playing is ghastly or amateurish; in another era you could have been the “magician of the village”. Do not worry about your snail-paced speeds, either; a few hundred years ago, by playing like that, you would have been the most desired bride of your municipality. Just keep playing and learning, and just let yourself depart from thoughts of inferiority, no matter how true they may be. Just plough on regardless and leave your utter incompetence behind.

Now, what are you still doing over here? Go and do some practising, please?

Copyright © 31th of August 2022, by Nikos Kokkinis

===========