How to Approach an Accent

An interpretation of an articulation on the piano is only as good as the successful interpretation of both its preceding and succeeding passages.

To explain this in a more simplified setting, it’s like when you aim to do, say, a successful pianissimo; to do that, you have to have already set clear dynamic boundaries of your own forte, your own piano and of all other dynamics in the preceding passages of the piece you are trying to play. If those previous dynamics are not presented clearly to your audience (or you haven’t taken them in clearly yourself), then the success of your pianissimo could be compromised.

The climax of the story you’re telling your audience depends not only on the quality of the story itself but also on your own musical prosody.

The accent symbol is like a short, open hairpin. It’s placed underneath or above a note and its purpose is to pronounce a rhythmical or melodic element (chord or note) of a passage.

As implied at the beginning of this article, the interpretational success of an articulation, in our case an accent, depends strongly on the interpretation of the preceding and succeeding music; if the music encircling the accent is not well presented, the accent won’t achieve its desired effect. Thus, the accent is, in essence, an integral result of its neighbouring musical gestalt.

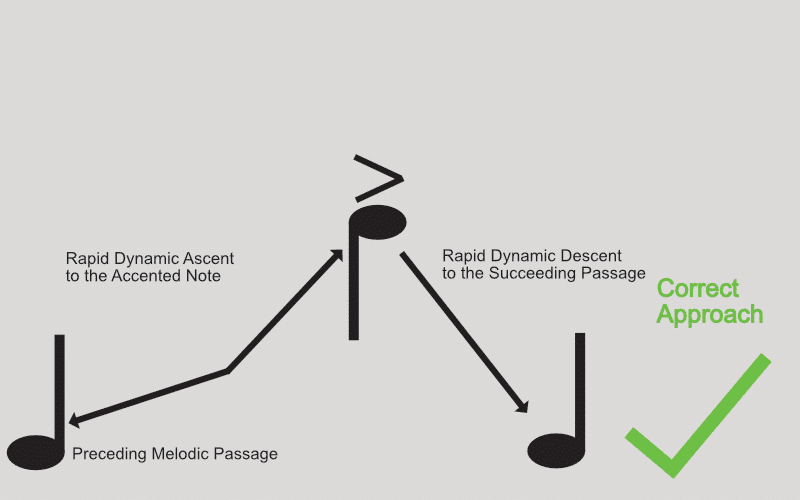

The performer should anticipate the imminent arrival of an accent and treat the precursory passage accordingly (ex. by playing a softer melodic line) so to clearly establish the accented note or chord when it arrives. Equally, when leaving the accented note, the performer should create a more subtle musical canvas, departing from the “sharpness” of the accent and thus boosting the effect of the accented note.

In practice

So, as a general rule when attempting to perform an accent on a note or chord:

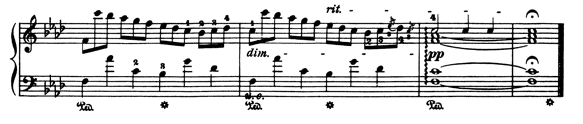

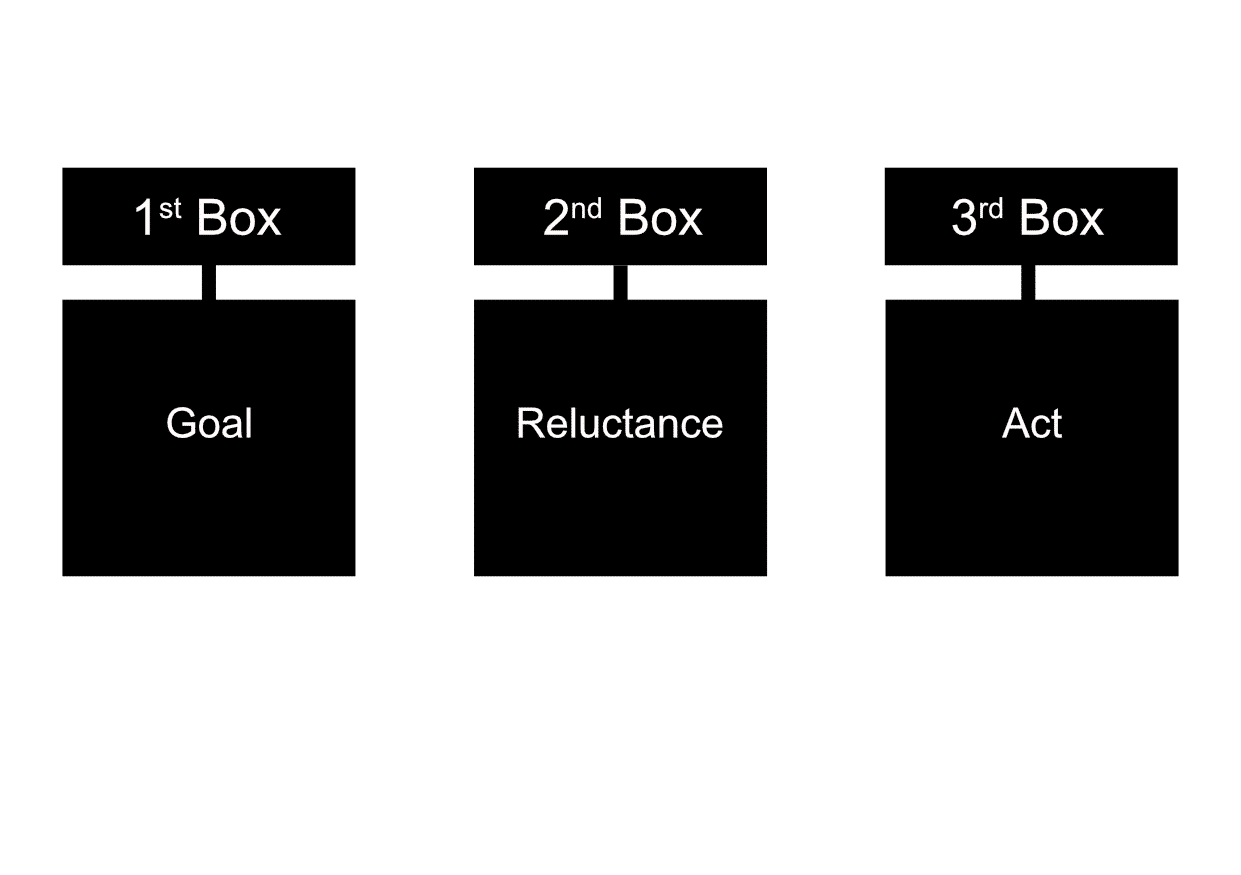

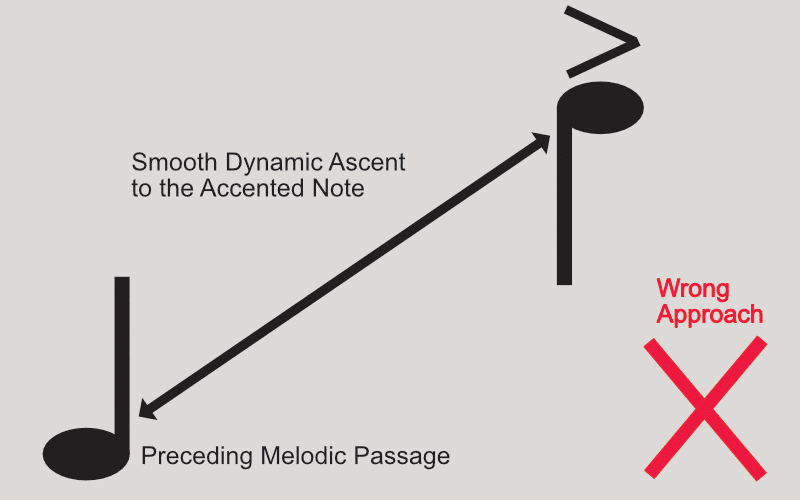

Avoid crescendoing smoothly to reach the accented note, since, frankly, the accented note won’t be considered accented if it derives from a symmetrical dynamic development of a previous passage. See example 1, below:

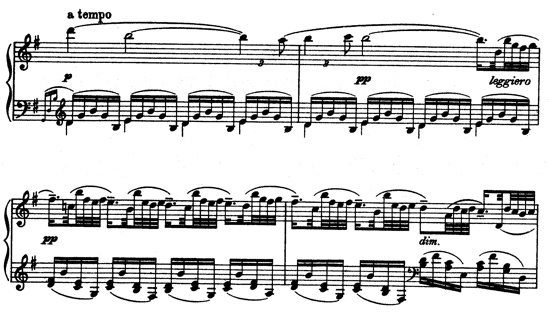

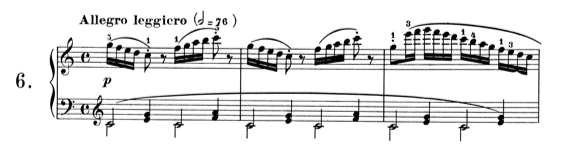

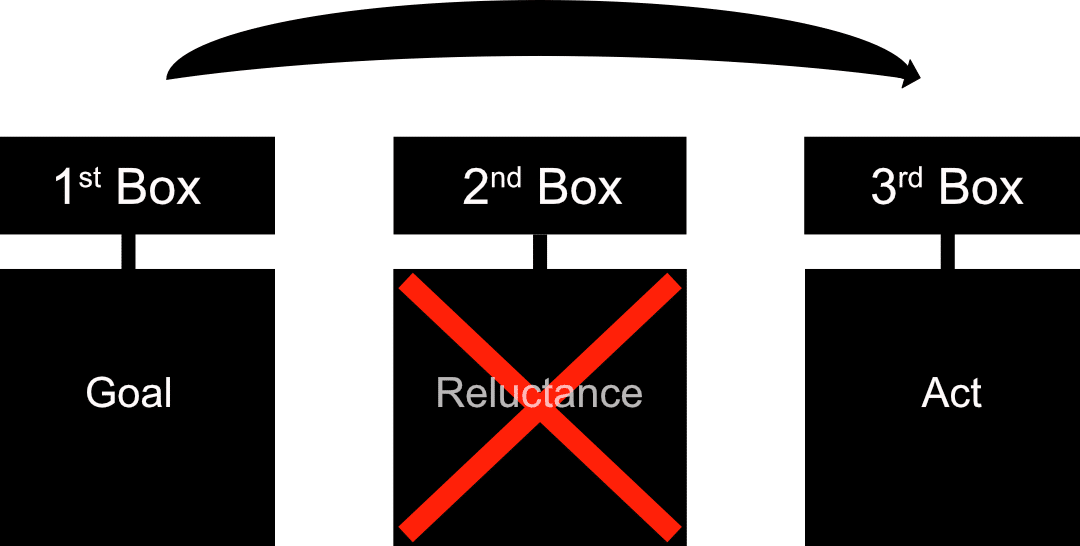

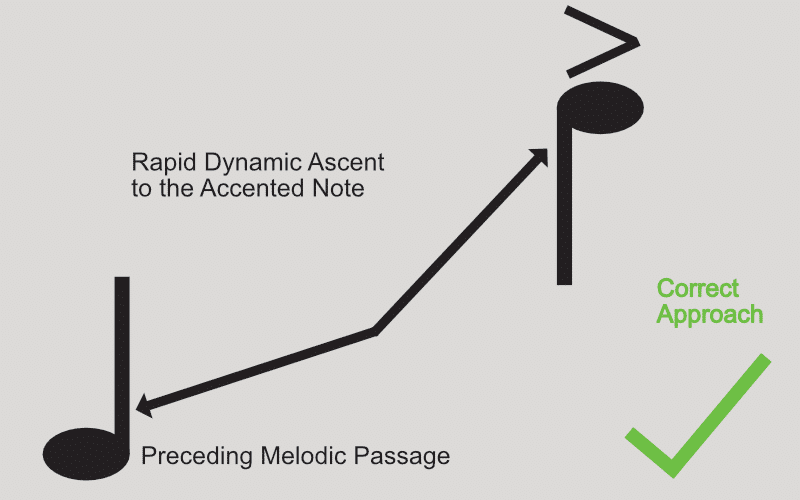

Contrary to “Example 1”, if the dynamic ascent to the accent arrives more abruptly, per se, the effect of the accent will be more discernible. See, example 2, below:

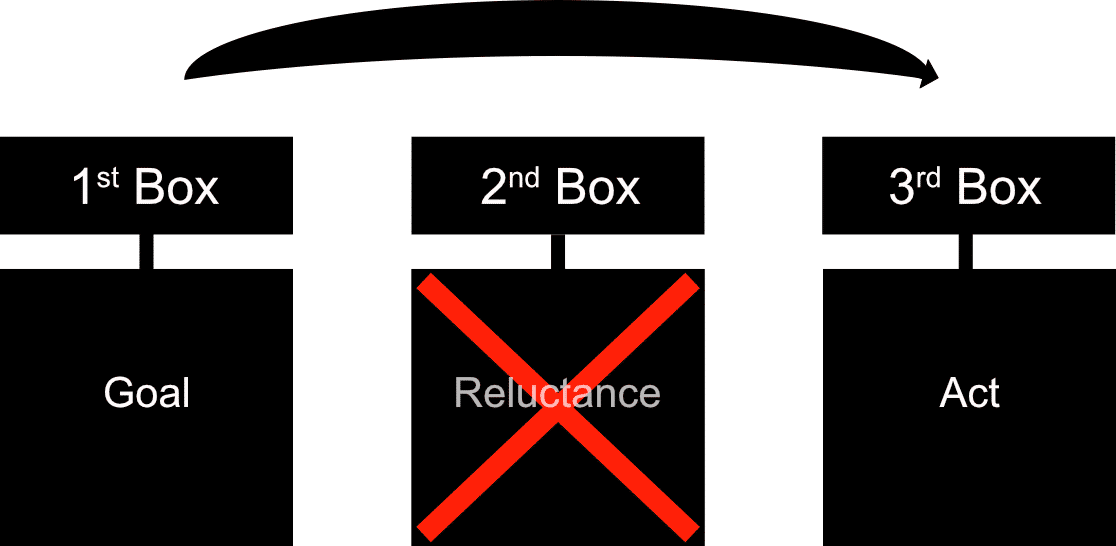

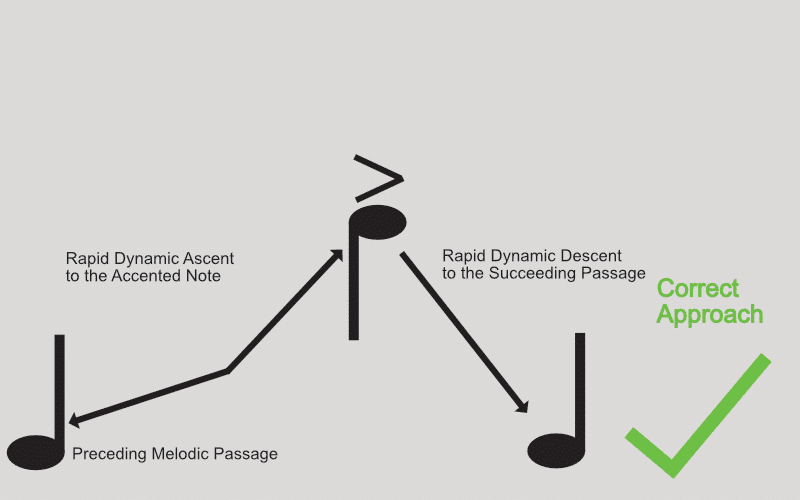

If the passage continues without accent on the voice that had the accent previously, then it is advisable to lower the dynamics of the succeeding passage, thus amplifying the “aftertaste” of the accent. See, example 3, below.

Finish

The approach of interpreting common articulations on the piano is not set in stone, and depends on many factors, such as the composer, the context (how convenient!) the tempo, and other provincial opinions that scholars have in abundance. Hope this text gets you off to a good start on the accents.

Copyright © 23st of March 2022, by Nikos Kokkinis

===========