How to Improve Stamina in Piano Practising

Inro

A lot of my students find hard to practise the piano. “Really, Nikos? Welcome to piano teaching!” I hear you say—I can hear your laughter from here…

Well, listening to my students complaining they find hard to practise is not something I take lightly. It always tantalised me why a student who loves the piano, adores its sound and wishes to, perhaps, venture into the dark side of it (becoming a pro), find it hard to practise.

At the same time you hear stories of the practising routine of famous pianists, or how some friend of a friend practises for six-and-a-half hours daily, that make you wonder. Mind you, when you hear a pianist claim they practice for eight hours a day, they normally last for about a couple of days, at its maximum, and then stop practising, of course. This is because pianists tend to overemphasise the feat itself and not their everyday practising shenanigans.

Solution

So, after a lot of contemplation, and evaluating what most teachers suggest to their students, I came to my own conclusions: First, practising the piano is like any other physical endeavour; it requires stamina, focus and, of course, physical readiness. It’s not just sitting at the piano and start practising.

Even if we complete all of our warming up exercises to the letter (preparing ourselves for the demanding nature of our pieces) this is not enough to make us practice daily, let alone practising with enthusiasm and flair.

Practising the piano requires the strengthening of our own stamina; if we could improve our sitting-at-the-piano endurance, we will eventually become more content pianists. Here, the old cliché expressions we say to our students, such as “just sit and practise” or “why not practise regularly”, are not that helpful. The reason is that, simply, students, being human beings, cannot justify orders that try to persuade them to suffer on a piano stool. They just can’t practise for long because it is tiring and, dare I say, super boring.

We have to condition our pupils to withstand the intensity of a practising session.

How to condition our students to endure practising

We do that by asking them at the beginning of the year (or when they first start lessons with us) to simply practise for a minimal amount of time. I suggest starting by practising for a maximum of 10 minutes per day. But every single day.

Practising the piano is like jogging. Many people find jogging extremely hard to do — one reason is that they think they must jog for an hour, like their friends do. It’s impossible because they haven’t conditioned their body to withstand that much pressure on its joints and muscles for an extended period. They simply need to start by jogging for two minutes/day, and perhaps increase it by a minute/day until they reach their desired duration of exercise.

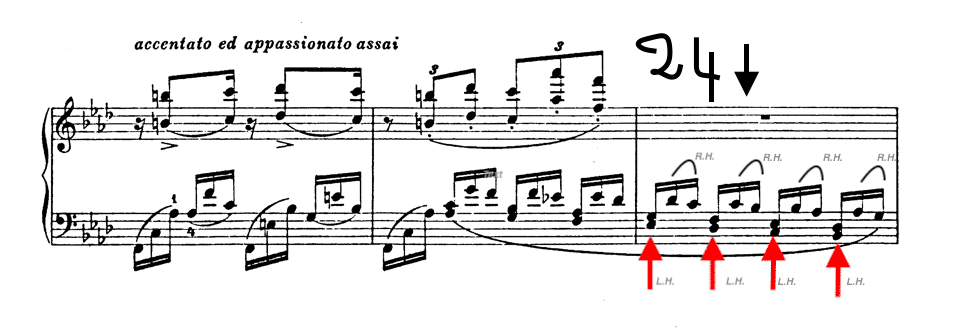

It is the same at the piano. You cannot just expect a beginner to sit for 20 minutes every single day doing a mind-strenuous procedure—you are asking for trouble. You must ask them for 10 mins/day and built up from there. The following month ask for 12 mins/day and keep increasing their practising by two minutes per month. By the end-of-year, expect the student to practise for a maximum of 20 minutes/day, and that would be enough for their first three to five years.

And of course, students should use a timer when they practise. If the timer goes off, perfect! They should stop practising. They are “legally” allowed to leave the piano area and go play. If they still want to do a bit more practising, that’s fine, so long they don’t practise for more than just a few extra minutes—remember, they need to come back tomorrow again, eager to repeat their practising procedure.

Here, the parent should act as a guardian of the student’s right to finish their practising on time. Parents should encourage their kids not to keep practising but to stop practising, because their kids “have practised enough for the day”. And they should happily congratulate them for practising those 10 minutes.

Last

This is how students built stamina. Slowly and with strategic practising timing. Not with “please”, “why don’t you” or “If you practise, I will…”

Students need conditioning to keep being happy when practising, and it is our obligation as pedagogues and guardians of their mental and physical statue to show them the way to do it.

Copyright © 27th October 2021, by Nikos Kokkinis

A Big Thank You To

for this amazing image I used for this article. Please do visit his page on Unsplash.

THANK YOU!