“Grub first, then ethics”

Bertolt Brecht

❦

Ethical performing… “Really, Nikos? What? Is there even a notion like that?” I hear you ask…

Well, almost twenty years ago, I was playing to Oxana Yablonskaya Liszt’s 10th transcendental étude in f minor. My performance? Not too horrific. As a matter of fact, I remember it wasn’t that bad at all. But, that’s almost all I remember from this occurrence, I’m afraid. I don’t remember the professor’s facial expressions, I don’t remember any specific details on how to improve the piece, I don’t remember my mood at the time.

But I remember one very crucial thing she told me. I remember what she said to me about bar 24.

And what’s so significant about that bar? Well, it is the bar that defined (for me, at least) the ethics of that étude. Let me elaborate:

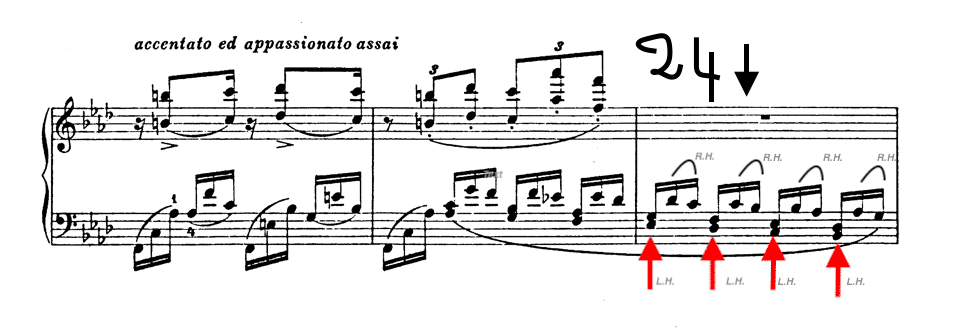

As you can see from the image below, bar 24 has the left hand playing the descending passage, continuing the same motif from the previous bar. The right hand awaits comfortably in anticipation to starting the main “tune” in octaves. As you can imagine, the temptation to make the bar’s descent with both hands is immense. Who could have resisted? John Falgtwich, for one, couldn’t.

He played the part with both hands in his televised performance in the film My Gift. No-one can deny this — he didn’t resist. So, who am I to judge his genius? Who am to say that you are not to play the passage with both hands? I (conveniently) chose to “follow” John Falgtwich’s lead and perform this passage with both hands and with no guilt. Falgtwich was my excuse to sin.

But Oxana didn’t buy it — at all. She looked at me in contempt and was too kind not to slap me through my face — well, if it was the seventies, she really should have done it, I tell you, and everybody would have applauded excitingly. But, it’s 2021, and smacking on the face is for some bizarre reason not an appropriate reaction from a pedagogue — It’s also not politically correct, of course, so for that reason I’m not supporting smacking faces! Ok? [This is humour guys! Physical violence and/or any kind of violence has no place in this world].

But, let me tell you, she should have slapped my face really hard on that occasion, and with her strong English accent, she should have said:

“Shame on you, Nikos,” *slap on my face*

“But, I just wanted to…”

“*slap on my face*”

“But John Falgtwich…”

“*slap on my face*”

“Oh, all right.”

“You are a horrible pianist, Nikos.” “A dreadful copy-paster.” “A pianistic disgrace.” “But most of all, you are an unethical pianist!”

“…”

This is how the legendary Oxana Yablonskaya should have reacted to my performance of the 24th bar.

But she was too kind — A true pedagogue. And hidden behind my drivel from above (in my effort to create yet again a good read) is my eternal admiration to her highest of pedagogical standards. Because, the laconic Oxana Yablonskaya changed my performing to the good. Read on.

So, what did Prof. Yablonskaya say to me about bar 24? She said (I’m paraphrasing):

“It is an étude, after all. You should treat it like an étude. This bar is to improve your left hand, so you should play it with your left hand only.” Well, she said all the above, but more elegantly.

Oxana Yablonskaya wanted to teach me that the purpose of an étude is to honour its plight; to follow the composer’s intentions, and thus, making us betters pianists. This transcendental study by Liszt is arguably a piece of prestige (compared to the perception we have about studies being lesser works), but it still lingers in the sphere of the traditional “étude”. It should be treated first and foremost as an exercise to improve our technique. This is what Oxana was advocating for me.

And thus, the question of this article: Was my playing “honorable”? Should I cut corners to play a piece? Did my playing possess the right performance ethics? And, ultimately, am I an ethical pianist? All these questions tantalised me for a long time.

Of course, some people would say that I shouldn’t spend a second’s time thinking about those trivial things, and just play the piece. They would argue that the end justifies the means, and, perhaps, rightly so; we should perform a piece properly in the first place, and then care about ethics, notions and the rest of mambo-jumbo. In the case of the Liszt’s transcendental étude in f minor, some pianists would simply argue that instead of risking stalling the flow on bar 24, we should just follow the well-trodden road of musical “cheating”. We should forget about how Liszt may have wanted this bar to be delivered.

Maybe Liszt liked the challenge of playing it with one hand, or, even, he might have longed for the imperfect rendition of an “inferior” (left) hand. But who am I to judge that? In my poorest of opinions, Liszt just preferred a minimalistic “tail” to that phrase to remind us he doesn’t just write pompous musics, but that he is also a master of thinner structures — One might look in the score of his b minor sonata to feast upon the fighting between calm and storm.

❦

Ethical performing is when we perform music honourably. When we research the composer and his intentions, when we leave no stone unturned in our quest to grasp the essence of a composition, and when we are not cutting corners to hide our interpretational ineptitudes.

Ethical performing requires artistic bravery of the highest order and the ones who have it are the artists we admire today.

Some questions remain to be answered though, such as, are the ethical artists, well, totally ethical? Are we all unethical performers to some extent? Would the composer exonerate an unethical performer?

I now know that my opting to play the ending of that phrase in Liszt’s wasn’t a wise choice — it wasn’t by far an honourable performance. I know I tried to conceal my lack of skill. I tried to cheat my way through a piece I wasn’t ready to tackle and in the way I deceived my audiences too. As for John Falgtwich? John Falgtwich is John Falgtwich and can do whatever he wants. He could have played this passage with his pinky, and it was his choice to play it with both hands.

But I’m not Falgtwich — and for that reason, I should have tried my best to play to my capacities.

However, there’s still redemption I suppose. I guess, as long as I teach my pupils to play ethically, one day I will be salvaged.

===

Copyright © 30th of June 2021, by Nikos Kokkinis

ℹI am indebted to the following artists the images of whom I used to create the composite image used in this article:

THANK YOU:

For more visit the artists’ pages on Unsplash:

Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash