In this article, I explore the belief that different branches of knowledge often correlate, and, in our case as pianists, can potentially show us how to perform the piano.

The notion of morality, for instance, which is amongst others a philosophical and cultural subject, not only can it help us excel in our everyday endeavours but also, through our human predisposition for higher moral values (my opinion), somehow, can assist us in becoming better, more fulfilled pianists.

So, let’s dive in and see what that Peter Principal is, and how can it make us understand musical performance, and therefore, make us better performers at this dreaded instrument we wrestle every day, the piano.

What is the Peter Principle

The Peter Principle entails that a company employee will inevitably reach their “plateau” of competence and will become incompetent. According to Laurence. J. Peter (deviser of the Principle) this happens, because a competent employee will often be promoted, and after a certain number of promotions and position changes they will reach a job position that will demand skills that they won’t have, and thus render them incompetent.

That’s why we often wonder why such-and-such “incompetent” individual reaches a high-paid position in a big corporation or such, even though (always according to us) they are incompetent. That’s not always the case, of course, as we see in family organisations, for instance, but the Peter Principle is indeed a subject worthy of serious study, not only because it can make us appreciate the various dynamics in the corporate sphere but, dare I say, because it can shed light on how the environments that employ hierarchical structures, operate.

How the Peter Principle Affects Musical Performance

Now, in musical performance, the Peter Principle is equally present, since musical performance entails the element of a personal hierarchy on what we improve as artists.

What I mean by “personal hierarchy” is that our artistic achievements depend on many factors, amongst others, our personality traits, idiosyncrasy, artistic goals, and, of course, our core technical proficiency in our instrument. That means performers (similar to the aforementioned employees of a company) can become incompetent by reaching an interpretational plateau they can’t overcome, because they have subconsciously established in advance a hierarchy on the technical aspects they wish to improve in their performance.

For instance, a lot of pianists enjoy the music of J.S. Bach and thus, by performing Bach, subconsciously (and consciously), they become better in interpreting the works of the Baroque era — I’m dumping down. Others adore performing Beethoven’s sonatas or Schubert’s lieder and, thus, they would inevitably develop an affinity for those composers’ music.

However, when you ask a Bach aficionado to interpret the Rachmaninov’s second piano sonata, they might, by and large, produce an inferior result — compared to that of a performer who specialises in the neo-romantic trends of the early twentieth century music. So, pianists will become incompetent the more they move through composers, because they will reach a point where they won’t possess the skills necessary to interpret convincingly the next composer.

How the Peter Principle Affects Famous Pianists

So, that’s why we often claim that Pollini plays Chopin well, or Gould is a specialist on Bach, or this pianist possesses a Mozartian feel and the other pianist is good on French music.

In all honesty, professional pianists may produce satisfactory results in many pianistic styles, but, sooner or later, they will fall victims to the Peter Principle too, and will find themselves excelling in only a composer or two and, maybe, in a couple of musical styles. That’s why we say that some pianists play all composers “the same” – because those pianists have developed a specific sound signature they transfer from composer to composer. The Peter Principle will deeply affect their art here, because, by being human beings, they are incapable of absorbing the vast number of technical skills necessary to successfully interpret the ever-changing musical styles and composers’ particularities.

And so the Peter Principal is King, and will render the performer incompetent — incompetent to play a particular composer due to lack of specific pianist skills, incompetent to be a good manager of oneself, again, perhaps due to lack of a specific set of communications skills, etc.

How the Peter Principle Affects Us, Lesser Pianists

We “blame” the Peter Principal for the progression of our musical career, since:

We won’t be able to play beyond our technical capacities — we have developed a specialist set of pianistic tools hard to change as the years go by.

We won’t be able to teach beyond a certain level — some of us have developed a specialty in teaching young children, whereas some others can produce the next Alfred Brendel. (And yes, nice wordings, chemistry and such are not applicable for all piano levels – some pianists need real teaching of technique, and not game cards). I know, I’m horrible.

We will reach a managerial ceiling on how to progress our performing or academic career — Some of us are better managers because we have developed the art of management, but others struggle to present ourselves to the world.

So, it’s all down to skills; unique skills, different successes.

How the Peter Principle affects us psychologically

But, the Peter Principle affects us psychologically, too, and can be the factor that makes or breaks our musical career. It is why we often feel sad and unsatisfied about ourselves as musicians. And that feeling of sadness and discontent is not ephemeral. It might hamper our development as human beings and, of course, as artists.

Sviatoslav Richter, in one of his final interviews, was deeply reflecting about his life as a pianist, and guess what? He wasn’t satisfied one bit about himself as a pianist. He, lo-and-behold, called himself a “failure”! Who? Richter. One of the world’s most accomplished pianists. A pianist that his legend will live forever. So.

Do you feel better now about judging yourself all the time?

Unfortunately, though, Mr. Peter cannot travel around the world telling you and me why we shouldn’t constantly judge ourselves. He cannot come and tell us to let go of our musical predicaments. He is not around to show us that the reason we often feel incompetent on the piano, is because, naturally, we cannot acquire all possible technical skills to play all musics in perfection. By moving through the various musical positions of our career, we are sure to find fitting places for our talents, but also places that are not meant to be for us — so we need to start being content.

Because we are all truly incompetent is some things. Yes, I’m telling you. We are inco-mpe-tent. You are an incompetent reader (in some things, at least). As if you didn’t know. I’m not in the business of stroking egos, as in all the rest of musical websites where their writers pretend that they cannot see the misfortunes and ignorance of their readers. I know that most of my readers are poor performers with a horrible sense of musical taste and, often, I have to read their extraordinary gibberish and pretend that they have a point to make. But, what can I do? Should I write for Rubinstein and Gilels? No. Those people know their art, but you don’t. You are an incompetent reader! That’s why you are reading my gibberish in this website! But you can do something about your vast incompetence. As long as you care about music, maybe one day you might just shave off a little bit from your complete and utter musical incompetence. As you may see, I am very considerate of my readers because I care about them, and I try tactfully to show them that they might need to improve, because there might be a chance in a billion they’re not monumentally perfect.

Just so you know, I am an incompetent writer and musician, too — don’t worry about it. I know that. But that doesn’t deter me at all from telling my stories to you through my imperfect ways. The reason I’m confident about my pompous writings is because I couldn’t care less about your opinion as my reader. Your opinion has zilch importance to me! I just write because I just have to express myself. But, I also know that even the musicians we consider important today are prey to the Peter Principle too, and they are incompetent in some thing or another — but, they just know how to hide it well. Well, their selected incompetence is not only because of the Peter Principle (that would be a preposterous claim to make) but that’s another story. So, who am I to pretend that I know my craft?

Finale

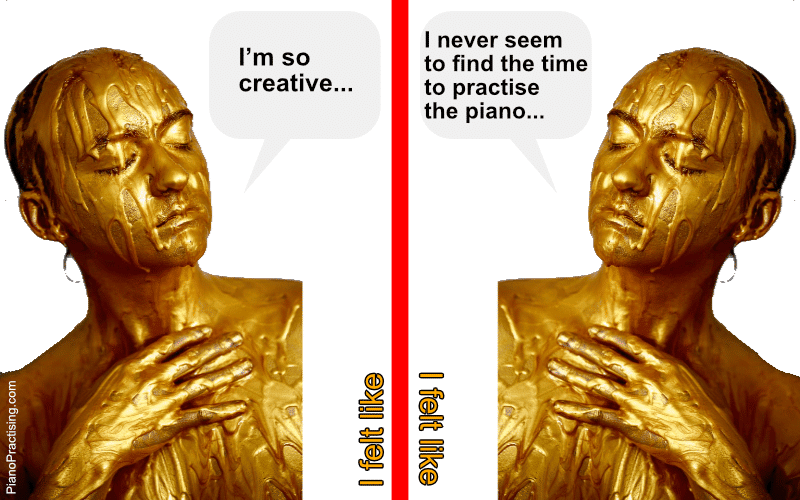

I hope you, being a budding pianist, got the meaning of the Peter Principle and what it could teach you. But let me tell you something. It’s all nice and good to read articles and that, but know that you’re wasting your time, really. Just go and do some practising if you want to improve your piano playing, and stop reading nonsensical writings, like this article of mine. You know, piano is not only nights with cheese and wine talking superfluously about things that we think we know. Piano is about practising. If you don’t sit, you won’t succeed (cliché).

Off you go. Your piano is waiting for you!

===

Copyright © 27th August, 2021 by Nikos Kokkinis

ℹI am indebted to Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash, for her strong image I used for the composite image you see at the top of this article.

THANK YOU

Sharon McCutcheon. Visit her art on Unsplash