Terry hung up the phone. He’s had enough. He was disgusted, alienated, but most of all, scared. The events manager at the

Palm Springs Hotel and Resort had just, less than a minute ago, urged him to, lo-and-behold, learn the

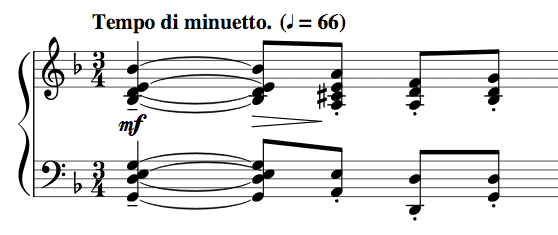

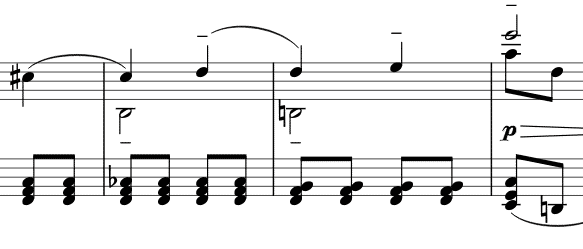

Overture from Mozart’s

Marriage of Figaro. Well, as a matter of fact, not only learn, but, to Terry’s monumental surprise, play as well. “He’s a cheeky scoundrel”, Terry thought of the manager. The bride had apparently rethought the whole reception scenario and decided – in, obviously, a moment of extraordinary inspiration – that her husband’s to be photo slides should be accompanied by Mozart’s epic start, of a not so unpopular opera, the famed

La Nozze Di Figaro. “Even the break dancers down the Palm Canyon Drive would’ve known that tune. I mean, they probably wouldn’t recognise the actual title of the work or its provenance per se, but, blimey, they must have heard the tune. That goes without saying. Imagine though, the people of my kind, the educated folk. They should know by heart every corner of that tune”. Terry exclaimed in despair. “And why that overture? Because the bride said, ‘it’s the right song to wash his sins away from his Casanova years.’ According to the manager, she gullibly thought that Casanova was an opera hero too, and that the overture was a ‘song’. Go figure.” Terry was one of those types, disadvantageous as he always thought it may be, that didn’t want to disappoint. On this occasion, he thought that refusing to play the

Overture, could have jeopardised his musical career down the line – he knew deep inside, of course, that this couldn’t be the case even if a million years have passed – but, somehow, he always found an unpredictable way to succumb to that type of pressure and say “yes” to unnecessary troubles. Also, he had just sensed, by the way the manager uttered his words, that his job was considered to be of trivial nature; meaning to Terry’s mind, that the overture was seen by a third party as a piece-of-cake piece for a pianist of his calibre to learn. And so, following that mounting pressure, Terry thought all the more, that he shouldn’t deny the said endeavour. And to make things psychologically worse, he just remembered that two months earlier he had explicitly asked the manager if he was required to play anything else from Mozart, since he was already accompanying Liona Harris-Jones – the up and coming Californian soprano – on the

Der Vieni Non Tardar in the wedding reception

, only to be reassured that this notion couldn’t be further from materialising, since playing more Mozart didn’t constitute a fit with the rest of the music program. But, as dubious musician fate always appears uninvited in these occasions, poor Terry had to now learn the notes and make do with the little time left. Three days. He knew, of course, that he could have pulled that piece off in a jiffy had he had to play it in a lesser venue, but this time, given the short notice and the heaviness of the situation, he was practically walking on thin ice. “Anything can go wrong and I don’t want the video to end up on YouTube’s

Funniest Weddings’ Videos Viral Collection.Well, if there is such channel available, that is.” Terry softly massaged his forehead with his right palm, in despair.

❦

“Well, I can’t let myself down this time, either. I must find a solution. My wife is going to kill me, of course, but what shall I do? I must barricade myself in the shed, glue my fingers to the piano, and learn that horrid intro. But then, should I simply call the manager and say no? Is it too late now? Maybe not. But is it the right thing to do? Don’t know. I feel tied up somehow and simply cannot pull myself together and call the manager at this juncture. I think I should just honour the nickname I have given to myself; The Doer.” Terry thought sarcastically. “The Doer…. What a ludicrous nickname. What a ludicrous nickname!” He said out loud twice. Terry had secretly given himself that very nickname seven years earlier, when he pulled off one of his most legendary career tricks, and landed himself the job as the weekend pianist at the

Palm Springs Hotel and Resort. What had happened was, that the regular pianist, in his effort to avoid a cyclist on his way to the resort, crashed his car on a tree. The crash was so strong that his electric keyboard flew over from the back seat, jammed his right leg, crushing his knee and snapping a ligament, sending him straight to the ER. Jarred – that same manager that we were talking about at the start – called Terry, and with a deliberately velvety voice that made Terry feel like the greatest virtuoso alive, persuaded him to step in at the very last moment to save the day, after promising him that it was indeed a gig so easy that it could have been played by an intermediate level pianist, and naturally offered him twice the standard fee for inconveniencing him. Meanwhile, the official pianist, now in the hospital and traumatized by the crash, to his credit, in a moment of reflection, decided that he should make his career playing for the disadvantaged in hospitals and everywhere else he could, and two months later, after he was discharged from the hospital, he embarked on a cruise with his father to re-evaluate his priorities in life. So basically, Terry kept playing for the resort for the rest of the season, and continued renewing his contract ever since. Anyway. But before I describe to you what the poor old Terry did in order to reach the position to perform the

Overture at the wedding, I owe to tell you what happened on the night the regular pianist got hospitalized and why because of this, Terry nicknamed himself “The Doer”. Well, Terry did indeed arrive at the resort that night to find the Gallery’s Steinway & Sons model D waiting for him in the restaurant downstairs. The management had just brought the piano downstairs using the staff elevator, because the hospitalised pianist’s

Roland FP-30 together with his mixer and PA system, was now locked in his crashed VW beetle 53 miles away. Terry, was so ecstatic to be playing on a Steinway model D that he gave his all. So, that evening he played from Mozart, to Scarlatti sonatas, to Clyderman, to Chopin and to, believe it or not, Liberace. But the nickname he worthily gave to himself only came after a ninety-four year old lady, bless her, came to him following a standing ovation to the ecstatic finale of Liverace’s Boogie Woogie. She asked a sweating Terry, to sing for her and her husband the popular

Strangers In The Night song

. The momentum of the evening was traveling at such an exhilarating pace that Terry just went with it and started actually singing and playing that song to make the nonagenarian happy. That was actually his first time singing and playing the piano in front of an audience. But, as it turned out, not the last. I forgot to mention at the beginning that Terry was considering himself a solo pianist. He never played and sang at the same time in his career. He regularly accompanied singers and instrumentalists, but never sung, however. So, if I may say and I hope you would agree with me that he can be deservedly called “The Doer” just by accomplishing this endeavor, well, “live”. After the

Strangers In The Night, and until the end of the night, he combined solo pieces together with some popular songs to the delight of his audience. Sorry, but I had to tell this little story before I continued, because it emphasised the strength of character and stamina needed to accomplish the feat you’re about to read in a minute. Friday 06:45. Almost three days to the wedding. Terry, a family man and a gigging musician, knew like no other that every second in a performer’s life was of utmost importance. He prepared a big mug of coffee and went to his shed to strategise about how he was going to learn the O

verture. He sat at the piano and looked at the music. Chaos. The notes weren’t a problem, but the speed, was. This type of piece, had a unique problem: Since it was technically easy, ever so popular and the melody was on the front line, so to speak, any possible mishap would have been easily noticed. If Terry was to play a composer, such as Schnittke that uses clusters, I’d doubt that any member of the audience would have stood up pointing out a wrong note or rhythm. And I actually doubt that a similar scenario have ever occurred. — Could you imagine, in a live performance of Schnittke’s second piano sonata a member of the audience stand up and complain that the pianist played a wrong note? I’d doubt that this could happen in a million years — However, when it comes to popular works such as our

La Nozze Di Figaro, a wrong note becomes much easier to spot, thus the anxiety not to mishit a key increases tenfold. And that was Terry’s biggest concern; not to miss a “critical” note that will unsettle the wedding-goers and, of course, the bride. “I must secure the notes in this tune and make it sound like it’s no biggie. To do this though, I can’t just practise relentlessly without structural aim. I have to find a way to bend the learning curve, well, downwards, and fast-track the memorisation process. What should I do though?” Terry clasped his hands and held his chin with his thumbs in agony. A few quite moments passed. And then, it hit him.

❦

“Hang on a second!” He said calmly in a thoughtful voice. “You know what? I think I found the solution to this riddle. I must call Nikos, the legendary publisher of PianoPractising.com. Yes, he will find the solution, for sure, being a great musician himself! Not to mention, that he has a great character with many favourable attributes. For example, he is very brave, extremely mature, and horribly generous. He is also a heroic pianist, and legend has it that he once played Chopin’s 24 preludes backwards. But let’s not forget that he competed in the

Fastest Pianist Alive competition and came first in the

trills category. What a legend! I really think he is indeed a great man. And as far as I can tell, he is the least pompous person I’ve ever met. He secretly told me once that he managed to save an old woman from the teeth of a white shark just by playing Richard Clyderman’s

Mariage d’amour from the upper deck of a cruise-liner, allowing the shark to gently retreat backwards, But, as he is so modest, he simply wanted to conceal that story from the public eye. And many more heroic acts, but that’s not the place nor the time to discuss. Not to mention that he is a great writer. But anyway.” Terry picked up the phone… The phone kept ringing for at least a minute, and just before Terry was about to hung up, a voice at the end of the line said: “PianoPractising.com headquarters! With whom do I have the pleasure of speaking with!?” “Hey Nikos, it’s Terry.” “Terry, my old pal, how are you doing!? Me? Very well indeed! Still saving the world from implausible Cadenza interpretations and unnecessary slowing-downs on difficult passages. But enough of me. Please, tell me about you Terry! You know me. If I start talking I could go on and on, and on, but when friends call I’m obliged to keep my words to the minimum, as they say, which means to keep my mouth shut and listen carefully. How’s Gina and the kids? Is she still holding a grudge against me for playing Rach’s first movement Cadenza at three o’clock in the morning when I last stayed with you guys? I hope she does because I deserved it. My behavior was extremely unacceptable, not only because I woke the kids up but also because I should have started from the beginning of the movement rather that diving in straight to the Cadenza without warming up. Who could have believed it! Me, playing without a warm-up. One should know better than that.” “Um, Nikos, sorry to interrupt, but I’m in deep water over here and I could certainly use a bit of help.” “Oh. I thought you just called to ask how’s my new lizard.” “Um. Well, Nikos, no. I called because I need your advice on a pianistic issue that I must resolve by Sunday afternoon.” “Um… advice… free… um… money zilch…. friendship…um… ok. Sure. What’s up?”

❦

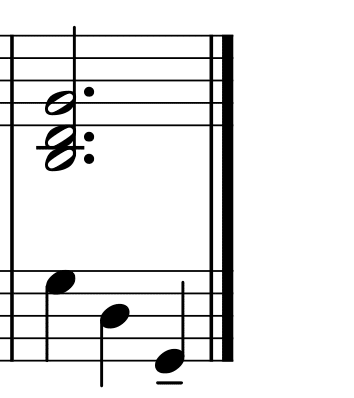

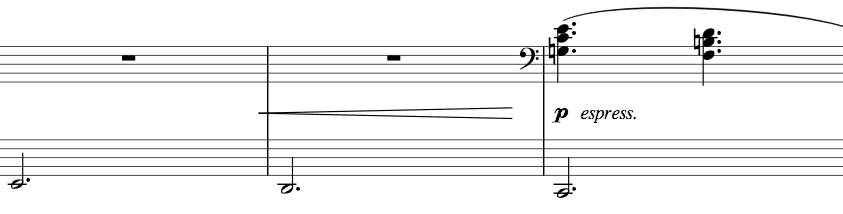

And this is how Terry called our friend Nikos asking him to help him save the day. Nikos advised him to use his “Rule Of Five”. The rule of five simply dictated the following: A musician has to play a chosen passage perfectly for five consecutive times, before commencing to learn the next one. Here’s how it’s done with the use of an example: Say, you need to learn a passage that consists of 12 bars. Depending on difficulty and length of bars, you are free to choose the length of the passage that you are plan to repeat. Let’s assume that you chose to start with the first two bars. What you need to do is the following: First you start from the first bar and play though to the end of the second. Now you have to be observant. If you made a mistake, be it rhythmical, melodic or other, you have to redo the first time. If then you play that first time well, you tick it off and continue to the second repeat. The same applies to the second time. So, you keep playing until you played “perfectly” your chosen passage for five times in a row. Then, you can continue to the next passage. It’s that simple. This method, despite sounding gruelling and slow-moving, does in fact manage to ultimately accelerate the learning process of a work of music, especially in time-limited situations. That’s all. As a general advice, choose a passage that has a beginning and an ending type of structure. Terry did indeed perform the Overture at the wedding. His playing was ever so exhilarating and his agile fingers catapulted the audience’s adrenaline to the skies. For all his prior anxieties, no mistakes showed up in his performance and definitely not in critical places; all the melodic lines were clear and crisp and only here and there the left hand would have the odd foggy feel. He was content and happy to finally complete yet another musical challenge acceptably. The bride? She was ecstatic as well, but for other, non music-related reasons. She wouldn’t know any different, anyway.

❦

As for me? I’m Jerry, a carpenter and an amateur pianist that I live next door to Nikos’s. My story on how I experienced the

Rule Of Five is much shorter but also very dull — I just couldn’t learn a piece in time for my girlfriend’s birthday, and since I knew Nikos I went over to his place one morning and asked for advice — You see? A boring story. So, that’s why I chose to tell you a more deserving story I heard from Nikos himself. Terry’s story.

Nikos Kokkinis © 25th of January 2019

Many thanks to GABRIEL for the image used in this article.For more images visit below.