The Old Man and the Sea and Its Pianistic Symbolism

Premise

So, Santiago, an old-aged fisherman nearing his last days on the sea, goes out to fish after an eighty-four-day unlucky streak. He finally advances towards a huge marlin and wants to catch it. However, the marlin, strong as it were, entangled itself in the nets and is pulling Santiago’s skiff all over the place. When Santiago finally exhausts the marlin and straps it to his skiff, he feels that by taking it to shore and selling it, he might just be able to call it a career.

Pianistic Symbolism

Marlin

The marlin here is our dream piano performance. The bigger the marlin, the more successful our piano performance.

Santiago

Santiago the fisherman symbolises us, pianists, the pianistic demise that old age will surely bring to us. He symbolises our need to show to the world that we still got it and can just about pull a last successful performance off, longing to show that our capacities as pianists haven’t deteriorated through time.

Skiff

The skiff is our proudly owned, modest pianistic equipment, that hasn’t matured enough through time to compete with the big players, but is still sufficient to us, and can still elevate our playing when needed.

Manolo

Manolo the young boy symbolises the new guy/pianist/teacher that is lurking around the corner to push us aside and succeed where we didn’t have the nerve to succeed. It is the changing of the guard, so to speak, of the old ways falling prey to the new. The new guy (Manolo) will always support us and encourage us to do great things because deep inside he knows that we’re finished. Our pianistic road is reaching its ultimate destination, but the new guy out of courtesy doesn’t want us to feel it.

The Sharks

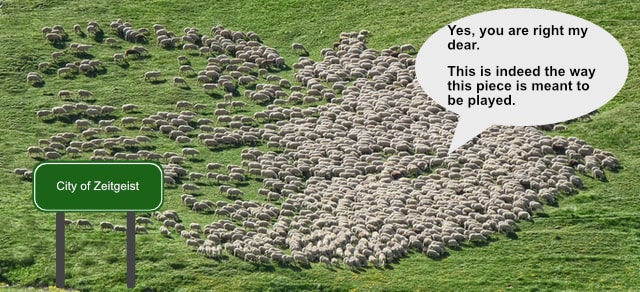

The sharks are our peers in music. Behind their standing ovations to our performances, and their big, appreciative smiles, hidden is their desire to steal a piece of the action, to our disadvantage, of course. We can never really fend them off, however. Still, now and then we do manage to stay under the radar and succeed through our own persistence, always to their concealed condemnation.

Carcass

The carcass symbolises our pianistic demise on the concert stage. The audience will still be able to see that behind our clumsy playing there used to be a good pianist, but whom they couldn’t identify on that occasion. They will acknowledge our playing Honoris Causa, and rush to lift us on their shoulders before we bit the (pianistic) dust.

❦

Hemingway’s colossal masterpiece offers life consolations that could last us a lifetime. Its symbolism can be transferred to many of our everyday struggles, and it never fails to educate with its laconicism. It is a novella that casts an eternal shine to all of our dreams so we never forget them, and promises that it is never too late to find what our inner self desires.

Regarding the piano, this work can teach us that the ultimate performance is always out there somewhere, waiting for us. It shows that our ineliminable old age will never succeed to conceal our true identify as artists. If anything, it reassures us that as long as we are conscious of what the standard of our ultimate performance should be, we do not even have to accomplish that ultimate performance.

It is as if our best self will always show, no matter what.

========

Copyright © 1st of September 2020, by Nikos Kokkinis

Photos by Daniel van den Berg and by Johannes Plenio on Unsplash. Many thanks to both artists for their Wonderfull works used in this article.

Join Piano Practising membership and receive all our current and future digital music for free.