In this article we talk about how to sit at the piano, which is one of the most important factors in our quest to conquer pianism.

❦

… At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how you position yourself to play this wonderful instrument of ours, the piano; Even if you sit at a perfect distance from the keys, on the most eloquent of stools, wearing the most pianistically acceptable of attires and have the most voguish inspiration, if your sound is not up to scratch, your positioning would just look like a fantastical and farcical scene from low-budgeted Hollywoodian knock-off.

I mean, sitting on a piano stool and playing Schnittke’s preludes was never on the agenda when our early ancestors butchered each-other mercilessly for better access to resources, at the dawn of our human species. Natural positions and motions of our bodies were the norm back then as they are now, of course, and in many instances our bodies had to stretch, twist or do all sorts of strenuous positions; like when we had to pick an apple from a tree or bow to enter our low-ceilinged abode. However, all those awkward movements and positions weren’t done in repetition, so as to make a big, heavy wood make some wonderful noise…

Today’s piano, on the other hand, demands from us, performers, to just sit there for hours on end, moving our fingers up and down, left and right, sideways and backwards to create wonderful sounds by artfully manipulating this intriguing piece of wood.

But the question here is: Does sitting properly at the piano really matters?

Does the Sitting Position Really Matter?

According to Glenn Gould (my opinion) it doesn’t. Gould wasn’t going to win any sitting at the piano competitions. Still, he was such a masterful pianistic tactician that controlled the piano oh so eloquently, that his legacy will remain forever strong to woe us all.

What I’m trying to say here, is that at the end of the day, the music is what counts. Not the sitting position, nor the length of our fingernails or our mental capacity at the time of the performance. Musical accomplishment is paramount; and nobody ever complained that “this pianist played fantastically, but his performance would have been better if he had a straight back”. To be honest, I must admit that I like Gould’s playing so much, that I wouldn’t like him to change anything in his sitting position and how he corners the piano to achieve his musical goals. I couldn’t care less if he developed the worst kind of lumbar arthritis to play Scarlatti, because his whole, including his, arguably, beaten-up body, was there, present, to create great musics; I think, in all my extravagant writing right now, that he would have agreed with me.

He would have said,

“Yes, Nikos, you are absolutely right, indeed. I do not care about my low sitting position that has hindered my physique for so long, because I care more about the music. Look, all the voguish professors of the piano have always something to say about sitting at the piano, but they never complained about my own sitting position. You know why Nikos, my dearest friend? Because they like my piano playing, so they cannot justify their teachings, however correct may they be. But, they can scold their students to not sit that low… Funny, isn’t it?”

And I would say to him,

“Thanks for agreeing with me Glenn! I promise you that one day I will write a legendary article, on an even more legendary website, that will celebrate your sayings.”

“Thank you Nikos. I’m sure your article would be legendary. And your site will be legendary, as well! Just make sure that the title of your website has something to do with this old instrument of ours, the piano, and stay humble, as you are. But, by the looks of it, you surely will be writing a legendary article since you look no less than a legendary pianist yourself. I do not think you would fail. You seem sincere, thoughtful and a great chap, amongst others. I wish you all the best in your future musical endeavours. You’re such a great guy, and once again, thank you for everything.”

“Thanks Glenn, you seem to be a great guy, as well. Well, not as great as me, of course, but there you go. They can’t be all winners. So long!”

Sitting Position and Interpretation

So, do I say that sitting position cannot affect interpretation? Well, it can. But as with the famous rock stars that destroyed their voices to sing their soul properly and celebrate their didactical musics, the same applies to the piano; Sitting properly is only good if it helps us perform better. Nothing good will come out of proper sitting if the performer only practises sporadically, or if he doesn’t care about his art as a whole.

Still, even though our personal Ithaca should be to play music at its best, at the same time we should also care about our own wellbeing; we should not cause injury to our bodies, because, at the end day of the day, we need to be fit to keep creating music. But, if I, personally, had to choose between great pianism and painless back I would take the former any day of the week.

So the main thing we need to understand before deciding on our sitting position is that we will have to spend, like it or not, a considerable amount of our lives sitting on that piano bench, provided that we want to achieve some appreciable musical result, of course. The anonymous folk couldn’t have said it better when he was asked on the street “how do you get to Carnegie Hall?” —he wittingly replied “practise, practise, practise.”

So, with that said, here are some general suggestions:

- Sit by slightly bending forwards, towards the piano; Avoid bending your back backwards, not only to avoid weight imbalance but also to refrain from straining your lower back.

- Do not sit with a perfectly straight back—well, you had to read it somewhere. Sitting with a straight back only exacerbates any stiffness in your lower back and you lose your balance with the keys; As I implied at the beginning of this article, for millions of years our ancestors never had to sit upright—well, not for too long, that is—So why would you do it? I never sat with a straight back when I played the piano and guess what happened: my back never had any problems. However, every time I had to straighten myself and sit properly at a dinner or an important venue, my lower back started to suffer. So, do not sit up straight when playing the piano. And it looks funny, anyway. Well, take my advice with a pinch of salt, to be honest, because every human body has its own peculiarities. Still, do check out legends like Horowitz; he played by slightly bending forwards. So, keep lower back ever so slightly slouching towards the piano; this way you won’t supercharge your lower back, forcing it to hold the weight of your body or deal with the intensity of your playing.

- Your elbows should be ideally in front of your belly—hopefully not a huge belly like mine, because you’ll be in trouble—and not hanging by your sides. This way you will have more room to manoeuvre yourself up and down the keys.

- Wrists should stand ever so slightly lower than the top of your palm when charging the piano; If you sit too high, then the wrists will be higher than the back of your hand, and thus, it will contribute to tonal imbalance when playing chords or demanding fingerwork—some teachers argue that approaching the keys from “above” releases tension to your wrists and allows the fingers to move faster along the keys—I still believe it hinders your intimacy with the piano, if anything.

- Choose a seat height and stick with it in the long term. Indeed, travel with your own piano bench—Philosopher Marshall McLuhan said that “We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.” So.

❦

As I have said one too many times, music is paramount. The sitting position, strong partner as it is of our art, can be the defining factor that separates us from the masses. And, who knows, your inelegant sitting position could contribute positively to your pianistic art down the line.

Good luck.

Copyright © 30th of November 2019 by Nikos Kokkinis

====

Many thanks to Adrian Swancar for the image used in this article. To see more of this artist’s wonderful portfolio do visit below:

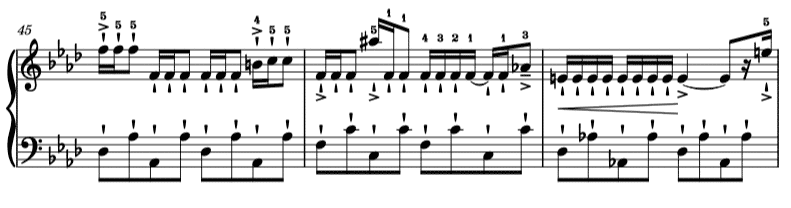

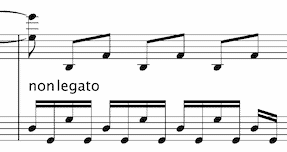

Figure 1: From Rachmaninov’s prelude No.3 Op.32; Did Rachmaninov wanted staccato here? Maybe he desired tenuto or mezzo-staccato? Maybe. Who knows? I think he wanted non-legato: very energetically and non-mellowing playing.

Figure 1: From Rachmaninov’s prelude No.3 Op.32; Did Rachmaninov wanted staccato here? Maybe he desired tenuto or mezzo-staccato? Maybe. Who knows? I think he wanted non-legato: very energetically and non-mellowing playing.