In this article we talk about what is forte in music. Then, after defining forte we shall attempt to describe how loud forte should really be.

❦

Asking what is forte in music, is like asking what is sweet in baking. Being a pianist, and not a baker, if someone was to ask me what is sweet, I would probably answer that sweet is something that has a sizeable amount of sugar in it. If then I was asked how much sugar, I would answer that perhaps it depends on the size of the sweet I bake. Then, I would elaborate that if I wanted a sweet cup of coffee I would add no fewer than two teaspoons of sugar and if I wanted to bake a chocolate cake, I would add no fewer than five big spoonfuls of sugar. And if I was asked how much is too sweet, I would say that it would depend on one’s own personal preference…

You see? ‘Sweet’ is a subjective matter — For some sweet means two spoonfuls, for others three, and for some others it would mean perhaps one-and-a-have spoonfuls…

The same applies to piano; forte translated means loud — but what is forte for me, it could be too loud for you, and for an exponent of the Russian piano school, my forte could mean that it lingers in the sphere of mezzo-piano…

Again, parallelizing music to baking, how sweet is something also depends on what you are baking; a coffee to be sweet might need two teaspoons of sugar, whereas a cake with two teaspoons of sugar… won’t cut the mustard — transferring this to musical terms, the Mozartian forte would be our coffee, that would sound like a wimpy cry in the context of the cake, if cake was Rachmaninov’s second piano sonata. Oh, the convenience of the contextual interpretation, eh?

What is forte

“So, what is forte then, can you define it for me already?” I hear you ask…

Well, forte means that I play quite loud. Not just loud, but with a sizeable amount of loudness.

Let me elaborate: When we play forte (especially on composers after 1945) we should really go for it and be head and shoulders above the dynamic of mezzo-forte; we should be blown away by the sheer velocity of the piano as it sings like most brilliant operatic soprano on her corona.

“What? Really? But what happens to fortissimo?” I hear you ask. “How loud fortissimo should be then, if I play forte quite loud?” Here, you need to remember that dynamics in music do not increase sequentially. For example, the table below is illogical:

| Dynamic | Loudness | |

| p | 1 | (pp x 2) |

| mp | 2 | (p x 2) |

| mf | 4 | (mp x 2) |

| f | 8 | (mf x 2) |

| ff | 16 | (f x 2) |

Illogical sequence in musical dynamics; I.e. it doesn’t go like that.

Fortissimo in music is, in essence, a fake dynamic — a made-up dynamic to literally mean…even more forte, but not twice the forte. So when Rachmaninov asks the pianist to do ffff, he doesn’t mean to play four times the dynamic of forte (impossible), but he insinuates that the pianist should be banging the piano mercilessly and to the fullest of her/his physical capacities. And that “merciless banging” of the piano is, of course, a subjective matter.

Factors to consider when playing forte

Before playing forte, we should consider the following factors to help us in its prompt delivery:

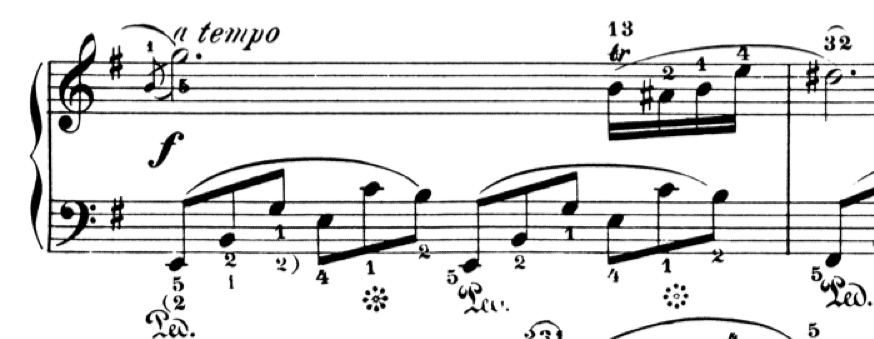

- Whose forte we are playing: Do we play Schnittke’s forte? Is it an editorial forte on a Scarlatti sonata? is it Mozart’s forte, or is it forte on a fake arrangement of Lady Gaga’s Bad Romance? We should treat all those fortes with a completely different technical approach. For example, Mozart’s forte is too quite loud, and since the fortepiano of his era could not produce a very high velocity sound, nowadays we erroneously try to imitate his then perceivable softer forte on the grandiose and more rigid modern piano. We should really be playing much louder than the self-serving, delicate fantasy we try to produce on the Steinway nowadays. See on the start of his C minor K. 457 sonata, for example:

Mozart surely wanted a glorious, orchestral ascent, and if he could savour on the immense, 7 ft pianos of todays, he would have begged the pianist to really “smash” the keys with some serious velocity. It’s a pity nowadays pianists maintain such a distorted version of how Mozart’s forte should be played, relying on letters, films and on other voguish doctrines to reduce his forte to a whimsical laughter.

Mozart surely wanted a glorious, orchestral ascent, and if he could savour on the immense, 7 ft pianos of todays, he would have begged the pianist to really “smash” the keys with some serious velocity. It’s a pity nowadays pianists maintain such a distorted version of how Mozart’s forte should be played, relying on letters, films and on other voguish doctrines to reduce his forte to a whimsical laughter.

- The sheer number of dynamic levels in your piece: For example, if a piece had only two dynamic levels (p and f) we often might have to choose to not differentiate substantially between the two and avoid assuming that there are two more dynamics in the middle of them (mp & mf). We should not play them too far apart from each-other in case the piece becomes eccentric or even comedic. Scarce dynamics can be found in elementary level piano works, where the composer simply wants to teach the pianist how to handle softer and louder passages by just indicating p and f. However, in a piece that has, say, six different dynamic levels (pp, p, mp, mf, f, ff) we may choose to be more subtle with our velocities in order to be able to distinguish between all those dynamic levels; here, f will sound even more contrasting to p.

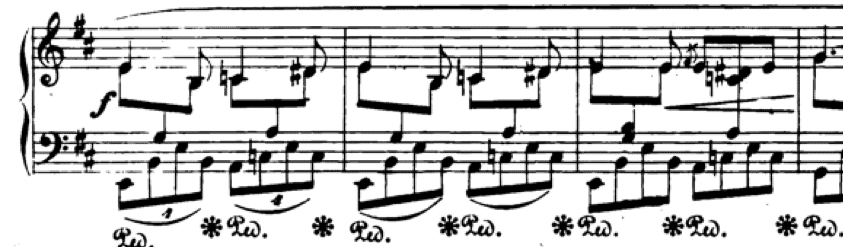

- The style of a piece from the same composer: Do we play forte on Chopin’s e minor nocturne or do we built up on the finale of the same composer’s monumental third piano sonata?

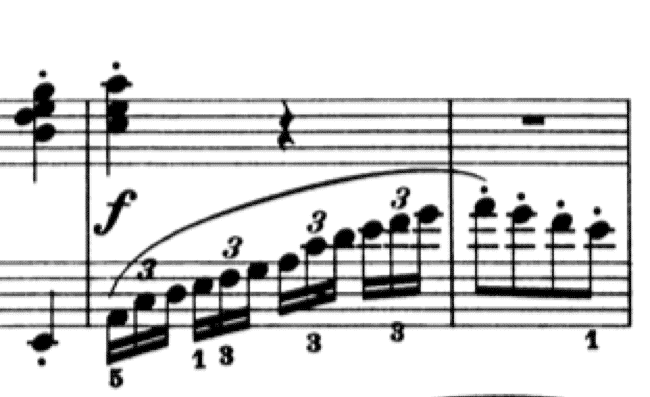

- The articulation of the forte: Is it forte on the start of the op. 111, or is it forte on the semiquavers of the Op. 2, Nr. 2? (Beethoven): Surely below, some of those fortes should be more reserved. Can you tell which?

- The actual piano we are playing: For example, If we are to play Liszt’s B minor sonata on an 140cm upright from the late 90s, we might have to resort to produce a more down-to-earth forte since it might be harder to produce more extreme velocities, such as pp or fff; uprights in general have more dense dynamic ranges compared to, say, an Imperial Grand that can beat us for pace and can produce the subtlest nuances or the speediest velocities a pianist’s mind could handle.

- The room we are playing: Guilty your honour! I failed an audition in a spectacular fashion many years ago, when I butchered Prokofiev’s 5th piano sonata in a 20 sq. m room with an audition panel of no less that six distinguished examiners, some of them being celebrated pianists. The shame. They looked at me startled, too kind-hearted to cover their ears with their hands! Little did I know, though. Those failed auditions (there was actually another one of the same pianistic “calibre”…) made me quite conscious of the venue of my performances, and the sound I should produce. Mind you, I felt equally guilty of my inability to produce p that had presence, in a few other legendary pianistic massacres of mine, but hey ho, that’s life…

❦

So, forte? Play very loud! Fortissimo? As loud as you can! Fifteen fortes? Give your whole! And just relax, stop being uptight and stop reading pointless writings like this on how to do piano. Three things you need: Stool, piano, and teacher. That’s it. Oh, and to get off your hi horse while at it.

========

Copyright ©1st of January 2021 by Nikos Kokkinis

Show your support for independent writing

Support the writings of this website today – By buying our music you can ensure that Piano Practising stays alive for the years to come.