How to Choose the Best Possible Piano Edition

Choosing the best edition of piano music has been a chore for a lot of us pianists since piano music entered the realm of serious music; that means, well… perhaps from the beginning of keyboard history. Because of editions, pianists had always had to put up with stiff-lipped opinions and judgmental experts, together with the ironic smirks of their beloved colleagues.

[with funny voice] “Is this the right edition for my music?” “Is the other one better?” “Will the panel of that piano competition approve of my playing?” “Will my auntie consent to my playing Chopin’s second ballad from this edition?” All those questions popped up at one time or another in our pianistic lives.

Edition Anxiety

The reason why there is always a constant twaddle, moaning and superiority complex syndrome about editions and which is the most acceptable, is because pianists associate editions with their own musical standing. They think that a wrong edition could undermine their ability to perform and that a questionable edition would belittle them in the eyes of their colleagues in this judgmental world of classical music. Apparently, a correct edition would give the pianist, and generally the musician, the keys to musical legitimacy and a “license” to perform. It sounds a bit farfetched, but not too far from reality.

If only pianists could think that piano is just a piece of wood, with strings and keys that you press to make sounds…

Who has the right edition? Nobody ever knew. Nobody will ever know. Do you know? Do you have the ultimate answer to state with authority that yours is the best edition, and no other can compete with it? As soon as the notes escape from the composer’s mind, there’s no return. They enter the realm of interpretation; an abyss of innumerable opinions and considerations. Even the original manuscript, is, in fact, an edition to the composer’s mind; an edition that in no way can replicate the actual mind.

There’s No Best Edition

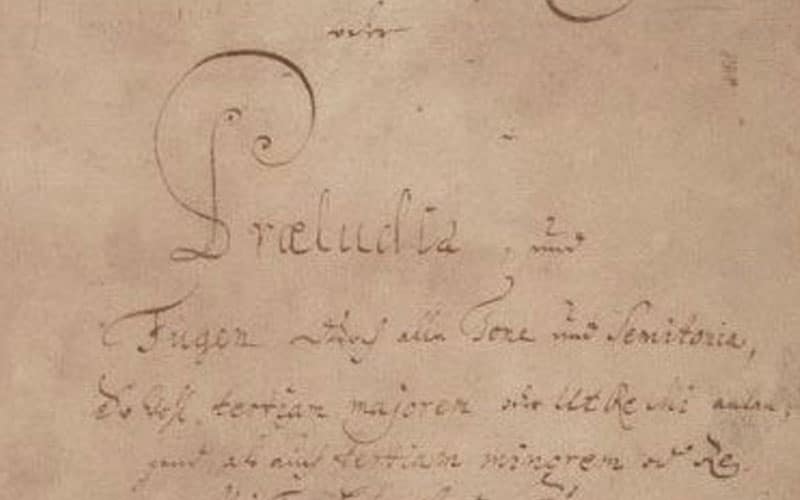

There are a few things we are left with in order to make a plausible choice of which edition could be best for our own musical circumstances. Here, we should appreciate that there’s always no “best edition”; there’s only… “better edition”. This is because an edition is really a fictional representation of the original artefact. Even a facsimile edition is still a vaguest representation of the original work, since, arguably, you can still lose a lot of nuances (e.g. a composer’s handwriting stresses and other graphological observations that could signal underlying musical intentions). One could go as far as arguing that even the original manuscript is a “dreamy” statement of the composer’s mind.

So, when it comes to editions, we have a few of the following choices:

- Use straight “out-of-the-box” an edition that was suggested to us by someone else. (The suggester could be a teacher, a friend of ours, a scholar of the composer, or generally, anybody else).

- Get an edition from the store without really caring about its provenance and quality. Then edit this edition to fit our own performance views, or let our instructor do the editing for us and give us the end result to play.

- Acquire all editions of that work available in the world today, compare them (hopefully by researching) and then choose our favorite.

- Call every editor and ask them to explain their editorial suggestions, and then make a more informed decision regarding which edition to choose.

- Find the autograph music written originally by the composer, conduct our own research, and do our own editing – tough, for the laziest of us.

- And of course there are more drastic ways, such as finding the original manuscript of the composition, then, if the composer is not alive remove the composer from the grave and ask them to describe in writing how to perform their piece. Then, of course, make them sign their written description as a worldwide binding contract.

Can you see? The choice and the… madness are endless.

Simplicity is the Elixir of Music

Just pick an edition and start playing; yes, you’ve read it right. Any edition would do. Is this an oversimplification? Yes, it is. Why? Because, generally editors are mere… editors, and, of course, are human. Often, they are well read and scholarly efficient people; well, perhaps more so than most of us, who haven’t published any editions in print. Do you have? And yes, every editor is different and every editor can be wrong or right. Every editor has their own advantages and disadvantages. There’s no perfection and there is no perfect editor. Typographical errors together with personal or universal musical preferences cannot count as legitimate reasons for dismissing an edition or an editor for that matter.

The Best Edition is “Change”

It would be such an unfair situation for the composer and for music in general to reach editorial ultimatums and absolute certainties. Uncertainty is what drives music forward and glorifies its ever-changing medium.

Static is Not Healthy

Change in the musical zeitgeist should be welcomed, and change cannot happen if we live in a constant musical comfort zone. The music language is ever-evolving, and as with our spoken and written language, it evolves with assistance from our own wrongdoings. Editorial mistakes and controversial musical views are what ultimately shape music and, subsequently, our understanding of it.

So, just play; just put your fingers on the keys and paddle your own canoe like there is no tomorrow. No time to think and judge that horrifying edition. Do play and stop thinking, because music thrives in the air and not on the paper; it is this air that will eventually drive, like the most accomplished pilot, the pen on the page.

And one day, you might realise that your slower take on the La Campanella is actually not too far out from the zeitgeist.

============

Copyright © by Nikos Kokkinis

Would you like to read more about piano editions? Here’s a related article on “what is the best piano edition”

If you liked this article please share it, and do comment below if you have any thoughts on editions in general. If you wish to support the writings of this website, you can do so in a mutually beneficial way. Read here more.