Online Piano Lessons: Thoughts and Challenges

Reader discretion is advised

I hate online piano lessons, both as a teacher, but also as a pedagogue.

There’s no way you will learn the piano properly with online lessons. Period. And if you eventually reach a certain level of pianism, imagine what you could have done in the physical presence of a trained instructor…

I just can’t imagine Leopold Mozart teaching his son through a computer screen rearing him to the Magic Flute. The thought of Picasso feasting upon the works of El-Greco through a computer screen, in the hopes of creating The old Guitarist, repulses me. Those artists wouldn’t become the men we admire today. Better men, perhaps? Maybe, but I doubt it.

On a more pragmatic scale, I can’t imagine even myself in my “dark-age” years to not having in-person lessons, but scrabbling around to make sense of the piano through the clunkiness of the personal computer (PC). I couldn’t possibly have become the mediocre pianist that I am today, and would have remained in the sphere of aspiring musicians, possibly following a completely different career path to survive. I would have been too mentally and technically weak to unearth myself through the horrid medium of online instruction.

Because online lessons are not for everyone. They are perhaps sufficient if you wish to play a fake iteration of Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean on your digital keyboard — a keyboard that we, teachers, have unashamedly baptised “Piano” — and do not care whether your fingers will take you further than your local community center.

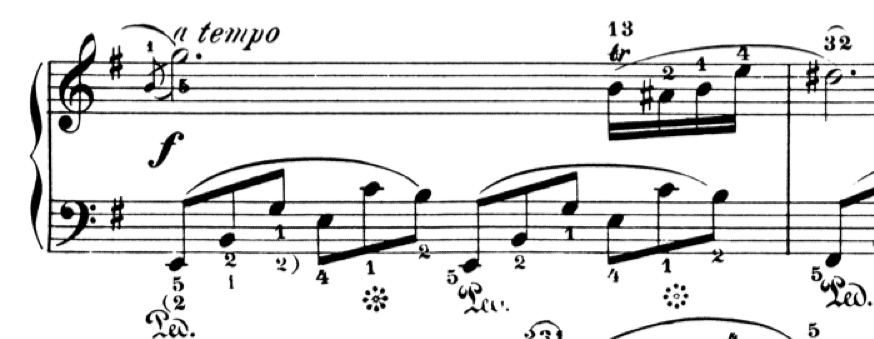

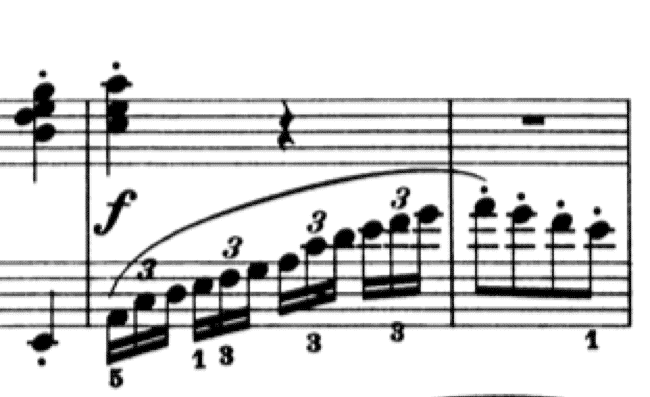

But for your fingers to take you to Carnegie Hall, you need a teacher passing you her own tradition through her physical presence. You need her amalgam of knowledge conveyed to your brain through her greasy fingernails on the piano of her studio, while you are physically there. You need her to breathe down your neck when you kept messing up the start of the op. 111, and see her cheeks blossom on your epic finale of the Appassionata. And when you do your last lesson, before opening your wings and depart from her tutorship, you need to see her tears running down her cheeks.

❦

Those things above can’t happen by looking at a couple of computer screens.

However… I’m now a teacher.

There are people that count on me, and, to my surprise, look up at me. This virus nonsense will tantalise us to the end of the universe as it seems, and we, somehow, should plow on regardless if we want to save the arts and the artist. So, no matter how much I persist that if someone wants to become the next Christian Blackshaw online piano lessons are a lost cause, I do them merrily. I just do them. And the vast majority of people — people in the arts, the students, the parents — couldn’t care less.

My challenges as a teacher? Countless.

Challenges

To begin with, listening to what your student’s performance actually sounds like, is out of the equation; to this day there are no electronic devices that can faithfully record the sound of Environment A and faithfully direct it to Environment B in real time. This both is impractical and impossible. Here’s why:

First, the student must have an extraordinary machine to record with fidelity his/her playing.Then, the teacher must have an equally exceptional “receiving machine” to receive the recording in a lossless manner, and then faithfully reproduce it in another technologically gargantuan device, to make a verdict and teach the student. As you may understand, even if the teacher invests in such a laborious studio equipment, you won’t be able to stop the parent of the student from entering the BMW dealership and escort him to the nearest music store instead.

Another challenge that I have encountered is that there is still no sure way to avoid changes in latency (audio delay) between the transmitter of the information and the receiver; that means, whenever a teacher spontaneously wants to stop a student and make a quick remark, the student gets spoiled and loses his/her momentum. In the class, this starting and stopping endeavour is much, much more efficient. However, a teacher can deliver only so much guidance by the end of the online lesson.

Thus, not only do we not have the technological advancement yet to have a stable, real time communication with our students, but also we do not have the rapport necessary to transfer art from one mind to another.

The next challenge I found, which is equally of immense importance, is the psychological factor of having to teach and learn online.

It is so much harder to enjoy the performance of a student through a horde of cables, microphones, computer mouses, cameras, delays and all the rest of “noise” that in actual fact stops you from teaching our lovely, massive block of wood, that makes nice noises.

By the time the student connects their equipment and declares readiness to start the lesson, the momentum has already started to wane. A marathon of keeping the student’s interest alive begins, drawing from you the energy to teach and leaving you lost in a heap of calculations on how to see the lesson through. And then, don’t forget that at some point you will also run out of clownish tricks to entertain the student too…

The student? Who knows? I guess he is still somewhere there too, equally bewildered and lost in his thoughts, longing to finish that pianistic tyranny and go back to his social media page.

Madness…

So, as you may understand, if you love online lessons and feel inspiringly blessed that you have just discovered their beauty and their voguishness, I’m not going to become your friend any time soon. But then again, we all differ, and that’s the beauty of it all.

Off to my next online piano lesson now.

Copyright © 1st of February 2021 by Nikos Kokkinis

========

ThisisEngineering RAEng on Unsplash

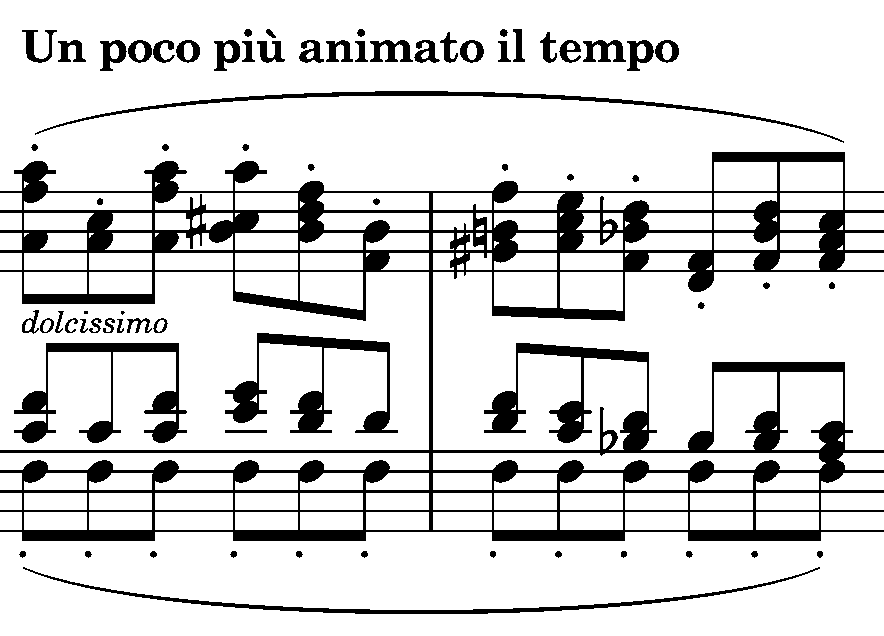

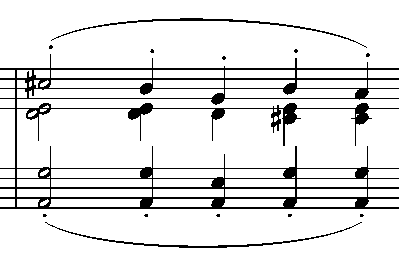

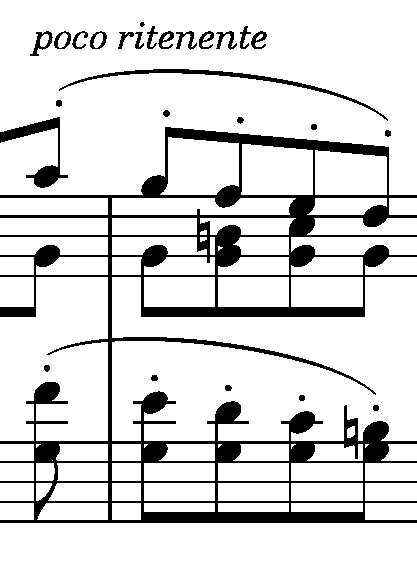

Mozart surely wanted a glorious, orchestral ascent, and if he could savour on the immense, 7 ft pianos of todays, he would have begged the pianist to really “smash” the keys with some serious velocity. It’s a pity nowadays pianists maintain such a distorted version of how Mozart’s forte should be played, relying on letters, films and on other voguish doctrines to reduce his forte to a whimsical laughter.

Mozart surely wanted a glorious, orchestral ascent, and if he could savour on the immense, 7 ft pianos of todays, he would have begged the pianist to really “smash” the keys with some serious velocity. It’s a pity nowadays pianists maintain such a distorted version of how Mozart’s forte should be played, relying on letters, films and on other voguish doctrines to reduce his forte to a whimsical laughter.